Welcome to our series on developing Critical Thinking skills, where we delve deep into the art of reasoning and argumentation. This week, we focus on the essential role of logic in studying arguments. Logic, the science of reasoning, proof, thinking, or inference, illuminates the principles that guide sound reasoning and scholarly debate.

By exploring this fascinating discipline, we aim to cultivate a deeper understanding of useful argument structures, aiding us in distinguishing compelling arguments from fallacious ones. Stay tuned as we embark on this enlightening journey into logic.

Table of Contents

2 An argument is something a person makes

An argument is a construction made by a person, often consisting of reasons or evidence to support a particular point of view. These reasons serve to persuade others of a specific claim, justify a position, or test the validity of a claim.

The strength of an argument largely depends on the logic, coherence, and relevance of these reasons and how effectively they are integrated to build the case. By mastering the principles of logic and argument analysis, one can become proficient in crafting compelling, persuasive arguments and discerning the quality and reliability of arguments made by others.

Good arguments comprise reasons or evidence to substantiate a point, whether constructed, invented, or borrowed. The purpose of these arguments is multifaceted. They might be used to persuade someone to accept a claim, justify a stance, or test the validity of a claim through examples.

An argument is not just a simple assertion; it carries an inherent purpose that drives the argument forward. This correlation between reasons and claims, wrapped in the purpose of persuasion, justification, or testing, forms the backbone of any compelling good argument.

III. Representing Arguments

An essential step in understanding and evaluating a valid argument is its representation. This process involves identifying and using complex arguments by clearly laying out the argument’s structure, focusing on the connections between various elements.

Take, for example, the first statement of the argument:

“All humans are mortal.

Socrates is a human.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.”

The first two statements in this argument are premises, foundational components that support the argument. The final statement, “Socrates is mortal,” is the conclusion inferred from the premises.

To represent this argument, we could denote it in the following way:

- All humans are mortal. (Premise)

- Socrates is a human. (Premise)

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (Conclusion)

By breaking down the original argument into its constituent parts, we can see clearly how the argument’s conclusion logically follows from its premises. This representation makes evaluating the original argument’s logic and coherence easier. Understanding this process of representing arguments also provides a powerful tool for developing our arguments and critically assessing those we encounter.

2 Critical thinking about things other than arguments

While arguments are a central focus of critical thinking skills, the principles of this disciplined thinking extend beyond argumentation. They can be applied to various aspects of intellectual and personal life, helping us make sense of the complex world around us.

One such application is in decision-making processes. Critical thinking skills aid in examining our decisions, ensuring they are informed, rational, and free from bias or undue influence. By systematically analyzing the options, considering the consequences, and evaluating the suitability of each choice, we can make decisions that align better with our goals and values.

Another area where critical thinking skills prove invaluable is problem-solving. Essential thinking skills can guide us in facing a personal dilemma, a professional challenge, or a societal issue. It encourages us to define the problem clearly, gather and scrutinize relevant information, generate potential solutions, and test them for viability.

Critical thinking skills enhance our comprehension and appreciation of various forms of communication, such as literature, art, and media. We can critically analyze a novel’s themes, assess a film’s messages, or evaluate a news report’s agenda. This deepens our understanding and fosters a more mindful and active engagement with these mediums.

Critical thinking skills extend far beyond dissecting arguments. It equips us with a comprehensive toolkit for navigating various intellectual endeavors, making informed decisions, solving problems effectively, and engaging more deeply with our world.

Critical thinking is key in determining government policy, especially in conservative government thought when parliament passes laws to resolve a country’s financial crisis cost. Making judgments based on a reasoned analysis of complicated situations and evaluating the available data are all made possible by policymakers’ use of critical thinking skills.

Evaluating Arguments

One of the most important components of critical thinking is evaluating arguments. This procedure helps us to thoroughly examine and evaluate the validity, soundness, and strength of an argument, improving our capacity to distinguish between arguments that are convincing and well-reasoned and those that are deceptive or defective.

Verifying the logical consistency of an argument is the first step in assessing it. If the argument’s premises and conclusion indicators are correct, we must verify that they would result in the conclusion that has been stated. If the conclusion indication does not make sense in light of the premises, the argument is flawed.

The veracity of the argument’s premises should be taken into account. If an argument’s premises are untrue, it cannot be sound even if it is logically sound.

For example, consider the following argument below, “

All dogs can fly. Rover is a dog.

Therefore, Rover can fly.”

Although the premise that “all dogs can fly” is untrue, the argument is logically sound. We can assess the argument’s accuracy and dependability by looking at how true the premises of such arguments are.

Last but not least, to recognize arguments, we must evaluate the premises’ adequacy and relevance. Do the premises and the single assertion or conclusion have a direct relationship?

Are they able to support it with sufficient evidence? Even if an argument has true premises and is logically sound, it is not good if the premises are unimportant or insufficient to justify the conclusion. We can assess the validity of an argument by determining its relevance and sufficiency by evaluating its premises.

Let’s look at an example to demonstrate this:

“It’s raining outside.

Therefore, the movie will be good.”

In this case, the conclusion is incorrect since the premise is unrelated to the decision, even though both the premise and the conclusion are true. We can determine the argument’s advantages and disadvantages by looking at the connection between the premises and the conclusion.

VII. Good Deductive Arguments

The validity and soundness of an argument are what define a good, deductively valid argument. Validity is the argument’s logical structure, which guarantees that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be as well. In addition to being valid, soundness ensures that the premises of the argument are true.

The validity of the premises of an invalid argument must inevitably lead to the truth of the other truths in the conclusion for it to be deemed deductively valid.

Take, for example, the claim that “all humans are mortal.” Socrates is a person. Consequently, Socrates is mortal. The argument must be legitimate if the conclusion is correct and the premises of the flawed argument are true.

Validity by itself does not guarantee a strong deductive argument. The argument needs to be strong as well. The argument must have genuine premises and be valid in order to be considered sound. Because the conclusion that “Socrates is mortal” must also be true, the argument is sound if we know that the conclusion that “All humans are mortal” is untrue and that “Socrates is a human” is true.

The structure of the argument (validity) and the subject matter (premises) of a strong deductive argument are both important.

VIII. From Deductive Arguments to Inductive Arguments

Inductive arguments

Unlike deductive ones, which are not about absolute certainty but probability and likelihood. Where deductive arguments start with general principles and apply them to specific instances, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. It begins with observations of specific instances and draws general conclusions from them.

We could infer that all swans are white, for instance, if we see hundreds of them and see that they are all white. Because the conclusion may still be incorrect even when the premises offer compelling evidence for it, this argument is inductive. A black swan might be out there that we haven’t seen yet.

Inductive arguments

While deductive arguments provide certainty, inductive arguments provide probability based on evidence. Both types of reasoning are crucial in different contexts and contribute significantly to our critical thinking skills.

IX. Inductive Arguments

Developing a hypothesis or theory based on observations is the main application of a strong inductive argument. Making predictions based on previous events is the basic idea of inductive reasoning.

For example, if the sun has risen every day throughout human history, we can infer that it will do so tomorrow. However, these arguments simply imply a high degree of likelihood rather than guaranteeing the truth of their conclusions, in contrast to deductive arguments.

When assessing inductive reasoning, it is essential to look at the caliber of the observations or evidence. The more thorough and pertinent the evidence, the more convincing the conclusion.

Nonetheless, it’s critical to keep in mind the fundamental drawback of inductive reasoning: even with a compelling argument, the conclusion may still be true or incorrect because

Inductive arguments come in various forms: prediction, inference from analogy, induction by confirmation, and statistical induction. Each form uses a single statement and a very different function and method to gather observations and draw conclusions, further broadening the scope and application of inductive reasoning.

6 Barriers to Critical Thinking Skills

Numerous obstacles to critical thinking frequently impede critical thinking despite its significance. These barriers may make it more difficult for us to thoroughly evaluate the facts and reach well-reasoned conclusions.

bias. The propensity to hold a skewed opinion that is shaped by our experiences, convictions, and values is known as bias. Our thought processes can be distorted by these prejudices, producing biased findings as opposed to impartial evaluations.

Assumptions. Often, we make assumptions without proper evidence. This can limit our viewpoint and prevent us from considering all aspects of a sound argument.

Emotions. Our emotions can interfere with our thinking process; such words often cause us to make decisions based on emotional responses rather than logical reasoning.

Over-reliance on Authority. Sometimes, we accept ideas simply because an authority figure presents them. This can prevent us from independently assessing the validity of these ideas.

Lack of Relevant Information. Without complete and accurate information, we cannot make informed decisions. Thus, lack of information or misinformation can greatly impair critical thinking.

Groupthink. This happens when we conform to the opinions and viewpoints of a group to maintain harmony and avoid conflict. This can prevent us from forming independent thoughts and inhibiting critical thinking skills.

How do you overcome the hindrances of critical thinking skills?

There are several strategies that one can employ neither the ability to overcome these barriers:

- Self-awareness. To overcome our prejudices, assumptions, and emotional impacts, we must first acknowledge them. To do this, we must examine how we think and deliberately seek out any influences that can distort our ability to think critically.

- open-mindedness. Being receptive to fresh viewpoints and ideas enables us to think about a range of options. We may be able to overcome preconceptions and prejudices and assess arguments more impartially as a result.

- asking important questions. One of the core components of critical thinking is questioning. We should investigate the ramifications of knowledge and validate it by asking insightful questions rather than taking it at face value.

- Seeking diverse viewpoints. Interacting with people who have diverse viewpoints can help us confront our assumptions and increase our understanding.

- checking and verifying facts. Verifying the correctness of the data we use in our reasoning is crucial to preventing us from making conclusions based on poor or missing information.

- autonomous mentality. It’s important to take into account other people’s viewpoints, but we should also draw our own judgments. This entails combining the knowledge that is currently available and applying logic to arrive at well-informed decisions.

What are the 7 principles of critical thinking skills?

The principles of critical thinking guide us in analyzing and interpreting information effectively. Here are the seven key principles of critical thinking:

- Clarity. This principle emphasizes the importance of clear communication and understanding. Defining and articulating the issues, questions, or problems you examine is crucial to avoid confusion and misunderstandings.

- Accuracy. Ensuring the information we use is accurate is essential. Incorrect data or misconceptions can lead to flawed assumptions and conclusions.

- Precision. This principle involves providing detailed, specific, and exact information. Vagueness can lead to misinterpretations and incorrect conclusions.

- Relevance: This principle underscores the need to use information directly related to the question or problem. Irrelevant information can lead to distractions and incorrect conclusions.

- Depth. Going beyond the surface level of information and examining the underlying details and complexities is vital in critical thinking skills. This helps in understanding the real issues and their implications.

- Breadth. The necessity of taking into account many viewpoints and concepts is emphasized by this notion. A more thorough grasp of the problem may arise from taking into account other points of view.

- Reason. Finally, the concept of logic demands that we make sure our conclusions are logically derived from our evidence and assumptions and that our reasoning is consistent. The nonsensical reasoning may result in erroneous results.

How do you find an argument in critical thinking skills?

Identifying an argument is the first step toward an argument analysis; evaluating many such arguments is part of learning critical thinking skills. An argument typically consists of a set of premises leading to a conclusion. The premises provide reasons or evidence that support the decision. To find an argument, one must:

- Identify the Conclusion. Look for the main point or the claim the author is trying to make. This is usually presented as a statement of fact, opinion, or belief. Indicator words such as “therefore,” “so,” “as a result,” or “hence” often signal the conclusion.

- Determine the Premises. These are the reasons or evidence given to support the conclusion. They can be factual statements, observed phenomena, or expert opinions. Look for indicator words such as “since,” “because,” “for,” or “given that” to identify the premises.

- Assess the Linkage. Examine how the premises support the conclusion. The relationship should be logical and coherent, without leaps in reasoning, fallacies, or unverified assumptions.

RELATED POSTS

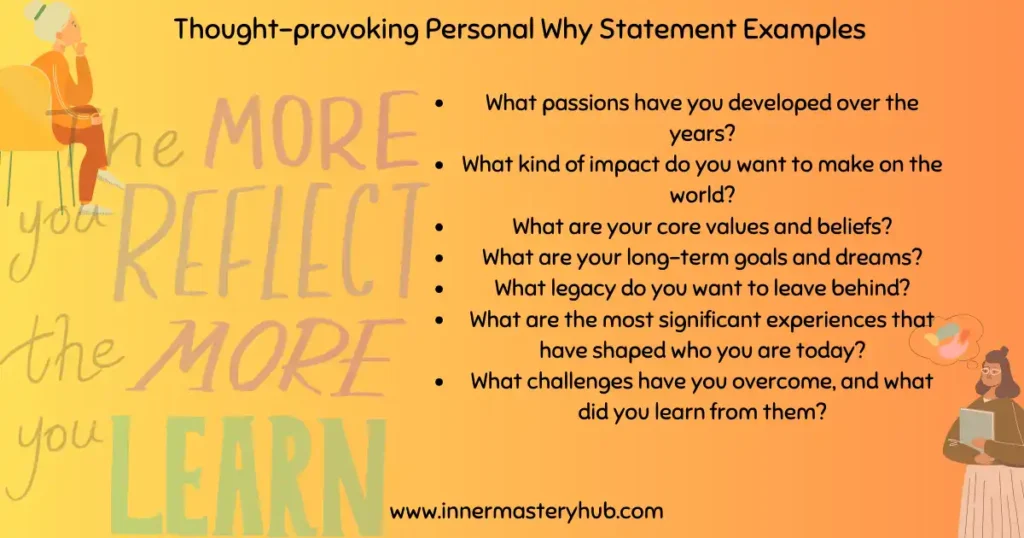

25 Best Thought-provoking Personal Why Statements & Examples